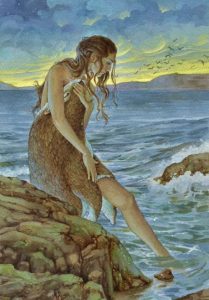

In Scandanavia there is a myth about seals which shed their skins to become women. The sealskins lie on a rock even as these naked women dance atop a rock in ecstasy. A man appears. Tears of loneliness had drawn chasms on his cheeks. Beguiled, he picks up a sealskin and negotiates with one of the women to spend seven summers with him. She agrees but, in this time, she weathers. He hunts, she cleans up after. Only a wisp remains of her untamed spirit towards the end.

On the eve of winter, in the seventh year, he tells her how happy they are, how their son is only a boy. But the seals call out to her invitingly. Come to where your soul is free, they say. She stays back in muffled torment. How could she leave the man who loved her unconditionally? He scolds her, makes her feel guilty. Now nearly blind and bent with age, she faces an even bigger hurdle. How could she possibly leave her son behind?

Her son begins a journey to recover her sealskin and returns it to her. Finally, she listens to the call of her heart. Her natural hide belongs in the ocean, her home. Instinctively, she picks up the boy and runs towards the ocean, breathing the earth’s breath into her son’s mouth. This bears him safely to the seabed where the other seals whisper the earth’s secrets into his ears. Then his mother tells him gently, “You are ready for the world. Go live. If you need me, call out to me and I will surely come.” Orook, her son, begins his life-story on earth. Wise beyond his years, ever so often he’s seen by the snow people – speaking to a seal by the seashore.

Four men enacted this myth at the workshop on the Sacred Feminine held at Untitled Arts on Friday, December 13th. They paused for a bit at the place where the women danced on the rock. It is a nativity scene. There seemed to be some tentativeness about the act- some awkward movements, some unexplored dialogue. This expression of tentativeness opened a space for collective reflection later. On the theme of desire there was a clear denouncement of sexual assault. Such men were declared villains. An exception was made about pleasure. Whose pleasure? Yours, I thought, enraged. ‘Ours,’ said a participant. The blitzkrieg of thoughts and emotions in my head, in my body, took to a bunker. There was something in that reflection that merited a more reflective stance.

When longing and loneliness meet soul and companionship for the man, there emerges a well-suited relationship. Everything seems well, until the woman’s truly wild nature calls out from within. The naked body stirs – robbed of its hide, of soul. It writhes under the pressure placed by the conditions – seven summers, a chained love, a child. A gnawing unease amplifies the woman’s muffled voice, making it sound as if it emerges from others located in the depths of the ocean. It is really her own voice, but it is projected out into the world as howling seals, a lost sealskin and the world for her becomes a mirror for the struggle within. For the man, the threat of losing his soul and companionship feels unpardonable, he resorts to aggression and blackmail.

While one participant’s response led to reflections on the conflicting needs of the man and the woman in the story, another participant spoke about desire and aggression becoming lust and violence. The recent gang-rape and murder of a young woman in Hyderabad, came up as a haunting reminder.

If love were unconditional and wild like the dance of the seals in the ocean, the resulting relationship would be one where each would transform the other engendering a spiritual romance. In this world, the woman can be a seal if she wants and the man can befriend his loneliness. That would be a Hierosgamos, or sacred marriage, as Carl Gustav Jung, a revolutionary psychoanalyst, calls it but that’s a difficult project!

One participant spoke about adjustments and assertions. In the myth, he saw his own struggle to adjust work and personal life. These were the seal woman’s struggles too. They were given the name of love, son and marriage. Indeed, our struggles engender guilt, soullessness and decay. I wondered about the mirror that exists within each of us. Everything that happens in the outside world reflects aspects of what troubles us within. And yet, like the seal woman and her husband, we start adjusting to the world outside and go about the daily business of hunting and cleaning instead of heeding the call from within.

A participant mentioned the allure of lustful advertisements which intensified the predatory sense in men. Again, my scathing politics was about to launch a barrage of accusations of being parochial, provincial and patriarchal. Instead I asked him about what went on for him within? There was no clear answer. The predators in Hyderabad had carried out a cowardly act of hunting and killing. Were they egged on by their own disquiet about a free woman, riding a scooter on the streets? We can’t know, and we can’t speculate as we are unaware of what really triggered the attack. Yet, we are struck dumb by the heinousness of it all.

The workshop for me triggered reflections on the process of becoming more and more conscious about our own unconscious demons. I wondered about the angry voices in my own head at that remark about advertisements. In the enactment of Sealskin with the participants, my own rage at the men who I felt hurt by found a voice that called out from the quiet compassion of the ocean. The men who caused the hurt and I were perhaps “unconscious” or “unware” of the things that were causing us emotional turmoil.

Including men in the discussion on finding one’s real voice singing from within was the goal of this workshop. There’s surely no better way to befriend the self than through the arts. I realize that this article may be construed to set gender binaries. But just as gender is about realising that there are binaries and breaking free from them; art is about finding that there is diversity and looking at ways to include everyone. Our work through Arts Practices for Inclusion is to walk together in these untrodden paths.