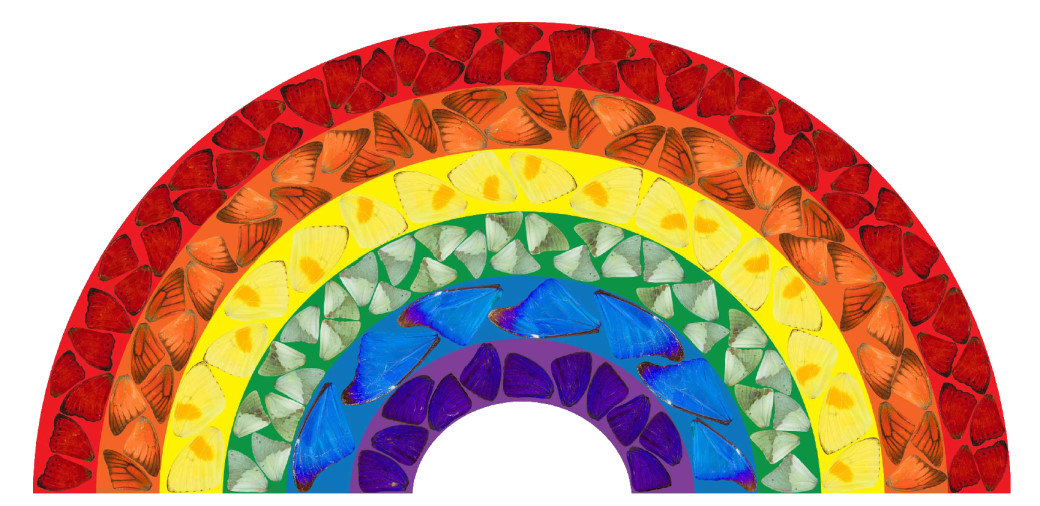

British artist Damien Hirst pays tribute to National Health Service (NHS) workers through this artwork. Titled Butterfly Rainbow, it shows a rainbow decorated with butterfly wings. He sees the rainbow as a symbol of hope and reassurance in the time of the Coronavirus pandemic.

Searching for inclusion in times of social distance

Each day into the lockdown, the news shows us the reality of how differently the lockdown has affected the poor. Even amongst the poor, the social, economic and medical reality of lockdown measures has led to a prioritisation of needs to be met by state and private persons. Notable among these are migrant labour. Large numbers of migrant labour are living in government run shelters even as states began sealing their borders in March. Some migrants were able to trudge hundreds of miles to make the journey home. Just yesterday, a twelve-year-old child died just about an hour’s distance away from home after making a 150 km journey from Telangana to Chhattisgarh by foot. A lot of the relief efforts for migrant labour have focussed on temporary shelter, food and money. But left alone, far away from home, migrants want to be at home with family, just like the rest of us richer or poorer people sitting wherever we are. Restlessness is palpable, anxiety is rife and concern for family members living far away is a continuing worry.

Amidst all of this, where is the sense of community and belonging? Sitting in closed spaces, camps or shelters, apartment complexes or slums among familiar or not so familiar faces, are people drawing comfort from their community or is community invisible now? First let us consider if there is any community at all. Two weeks ago, the Prime Minister called for a 9-minute blackout and lighting of lamps to express solidarity with all those self-isolating. Yet come 9 pm on 9 April, those 9 minutes saw people across the country lighting fires, firecrackers, Diwali lights and gathering in large numbers on the roads to celebrate in violation of social distancing rules. Sure, there were persons who quietly lit lamps at home, wondering about the safety and security of themselves and others, just like the volunteers at Caremongers- a Bangalore based Facebook initiative connecting those who need help with those who are willing to help. Within a month, Caremongers enlisted over 30,000 volunteers across the country. If the premature Diwali celebrations on 9th April showed the selfish and shallow side of the community, the story of an army of Caremongers’ volunteers who delivered essential medicines to an elderly woman in Mumbai exemplified a strong sense of community and belonging. Elsewhere a group of friends got together to build resilience in communities of daily wagers and slum dwellers in Guwahati, Assam by channelling crowdfunded money into provision of essential supplies.

As Indians, community plays such an important role in psychosocial wellbeing- joint families, relatives, friends are a vital support system. We almost always have people around us. This gives us a sense of comfort and reassurance that we have ‘our people’ to share our feelings with and an expectation that ‘our people’ will be there for us when we need them. However, a sense of community and belonging may seem difficult to trace from within closed spaces during the lockdown. We find out about how others are doing through phone calls, WhatsApp, social media, the news. Finally, even the physical presence of people on roads or housing complexes is masked and gloved, reminding us to stay away. In these times, what are we doing to offer a sense of community to those who need such support around us?

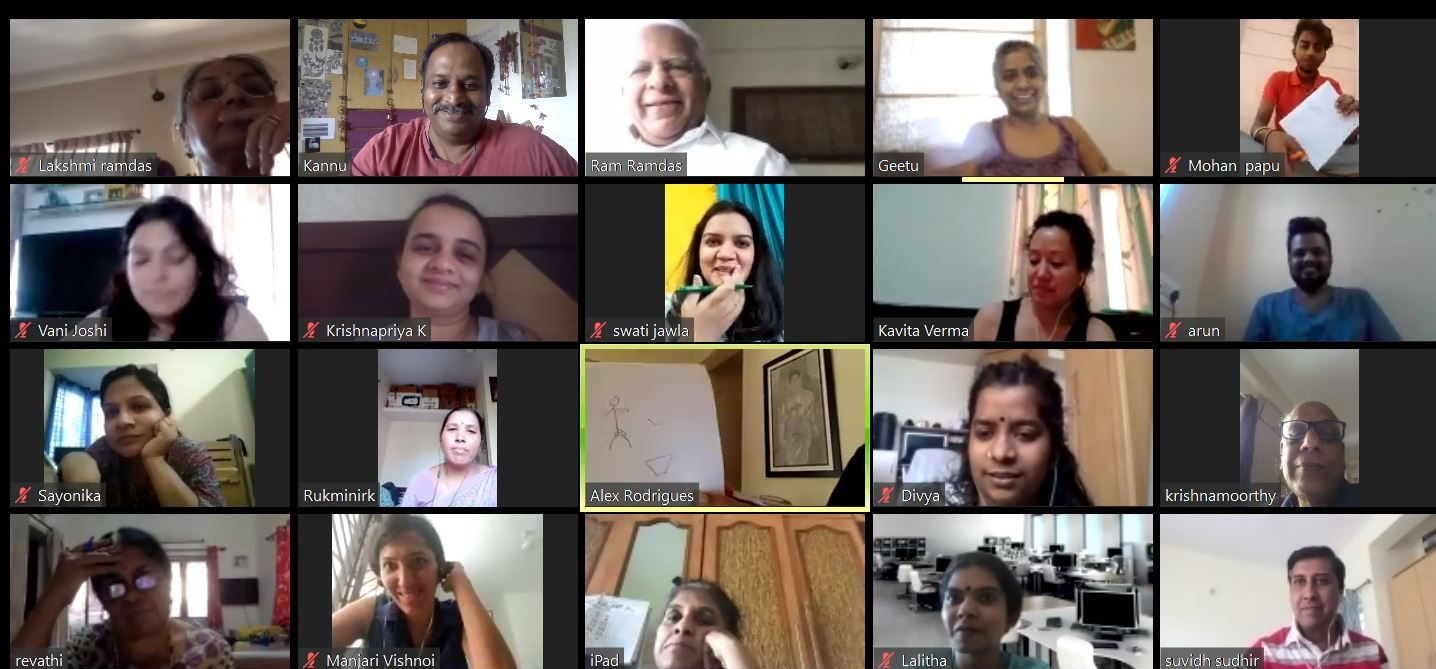

At Snehadhara, we found a host of different ways to do this through arts practices. We spoke to Gitanjali Sarangan, Founder and Executive Director of Snehadhara Foundation who cheerfully mentioned her ‘Reading Circles’ where she would pick out a story book to read to the neighbourhood children. The children and young adults shared how it has been long that anyone has read to them.

Snehadhara’s facilitators try to give their students a sense of inclusion in the school community even though everyone is at home. Virtual sessions are facilitated for each student twice every week in addition to Summer School sessions. Facilitators read stories, sing songs, cook, play instruments, dance, encourage and support functional learning through these sessions. Snehadhara’s parent’s community devotes weekly sessions to talk about sexuality education for children and adults with developmental disabilities. Parents also share moments from the Virtual Sessions between Snehadhara Facilitators and the students on a ‘Parents Only WhatsApp Group’ sharing the joy and excitement with other parents. The Supervisors on Prajnadhara’s Arts Practices for Inclusion Course are also beginning a journey of e-learning through the arts such that they can develop their practice and learning process in the field of social inclusion through the arts.

The arts are a wonderful way of connecting with others and offering a sense of community in times of social distance. Connecting and maintaining communication through the arts can be such a powerful way of telling others we are there for them, just as others are such an important part of us. The extended lockdown is an opportunity to build inclusion in a time of social distance.